Nonsuch Palace

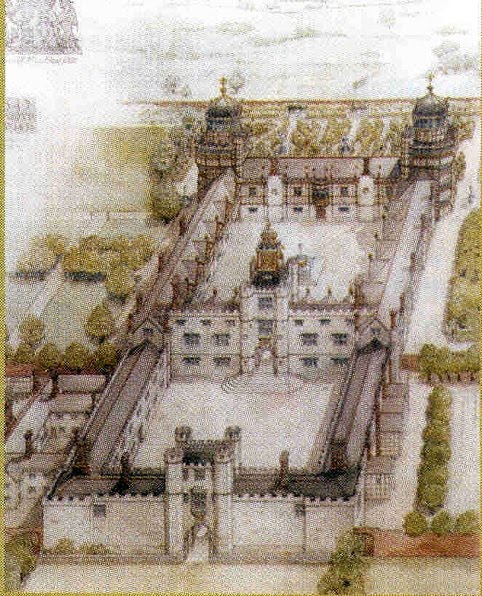

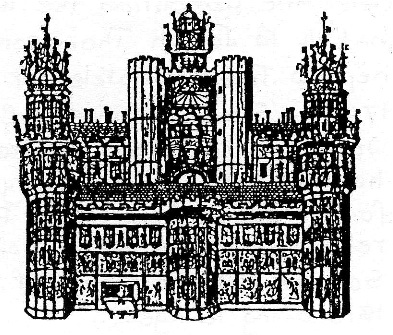

The birth of Henry VIII's sole surviving son led directly to the destruction of the manor of Cuddington. To celebrate both the securing of the succession and the advent of the thirtieth year of his reign, Henry decided to build a palace which would have no equal and call it "None Such".

|

o

Elizabeth and Richard Cuddington were given the manor of Ixworth, Suffolk and Henry set about removing the village of Cuddington. The only obstacle was Merton Priory which protected the church. One week before the building began the priory was suppressed and its stone used in the building of Nonsuch Palace. The building of the palace began on 22nd April 1538. By September the foundations were finished and around five hundred workmen from all over Europe were employed on the site. By all accounts, these men succeeded in building for Henry, the magnificent palace he had desired. It is, therefore, somewhat surprising that he appears to have visited only three times, twice in 1545 and once in the year of his death. His son Edward had little or no interest in the palace and Mary sold the palace to the Earl of Arundel. |

Arundel had only one child, Jane, who married John, Lord Lumley. It is her effigy along with that of her three children which can be seen in the Lumley Chapel next to St Dunstan's Church, Cheam. With his son-in-law, Arundel installed fountains and statues in the grounds and paintings in the palace. After Archbishop Cranmer's death at the stake, Arundel had acquired his library. This was to form the basis of the Nonsuch Library which was to become the second largest in private ownership. The royal connection with Nonsuch did not end with its sale. When Elizabeth acceded to the throne Arundel held a huge party in her honour, and thereafter, Elizabeth was a frequent visitor to Nonsuch. When Arundel died in debt Lumley sold the palace back to the crown.

During Elizabeth's ownership she spent part of every summer at Nonsuch where she enjoyed hunting in the grounds. Tradition has it that on one trip she stopped at Whitehall in Cheam to sign important state papers before returning to the palace. Elizabeth was the first and only monarch to devote a great deal of time to Nonsuch. James gave the palace to his wife Anne of Denmark, but it was his eldest son, Henry, who spent most time at Nonsuch, perusing the books in the library under the tutelage of Lord Lumley and hunting in the Great Park. Charles followed his father's example and granted Nonsuch to his consort, Henrietta Maria.

During Elizabeth's ownership she spent part of every summer at Nonsuch where she enjoyed hunting in the grounds. Tradition has it that on one trip she stopped at Whitehall in Cheam to sign important state papers before returning to the palace. Elizabeth was the first and only monarch to devote a great deal of time to Nonsuch. James gave the palace to his wife Anne of Denmark, but it was his eldest son, Henry, who spent most time at Nonsuch, perusing the books in the library under the tutelage of Lord Lumley and hunting in the Great Park. Charles followed his father's example and granted Nonsuch to his consort, Henrietta Maria.

The civil war had little direct effect upon Nonsuch. Henrietta Maria used it as a refuge when the Scots invaded in 1640 but there was only one small but bloody skirmish at the banqueting house in 1649. The interregnum saw the estate divided. Major General John Lambert was granted the palace and Little Park and Colonel Thomas Pride, the Great Park. The parliamentary survey of Nonsuch in 1650 noted that the estate was already in need of repair and by the time of the restoration the estate needed extensive and expensive renovations. On his mother's death, Charles decided to use Nonsuch to pay off his mistress, Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland. She was created Baroness Nonsuch and for the last time Nonsuch passed from royal hands.

Barbara Villiers found the palace to be a drain on her resources, so, to offset her large and increasing gambling debts she applied for permission to destroy the palace. A warrant was issued in 1682 and demolition began in earnest. Barbara Villiers outlived her son so it was her grandson, Charles, 2nd Duke of Grafton who inherited the estate. He too exploited its monetary possibilities by mortgaging and remortgaging the site. By 1731 his situation was so dire that Parliament forced the sale of his Surrey estates.

The Great Park was sold to John Walter, Grafton's former steward, and in 1750 was sold in chancery to William Taylor who established the Malden Powder Mills. The Little Park was sold to Joseph Thompson. On his death in 1743 the estate passed to his nephew, Joseph Whateley on the condition he take holy orders. It was Joseph's brother Thomas who resided at Nonsuch. Thomas was interested in landscape gardening and it is likely that he began to set out the gardens at Nonsuch. When Joseph died in 1797 his will instructed the sale of the site. The estate was finally bought in 1799 by Samuel Farmer.

.

.

Barbara Villiers found the palace to be a drain on her resources, so, to offset her large and increasing gambling debts she applied for permission to destroy the palace. A warrant was issued in 1682 and demolition began in earnest. Barbara Villiers outlived her son so it was her grandson, Charles, 2nd Duke of Grafton who inherited the estate. He too exploited its monetary possibilities by mortgaging and remortgaging the site. By 1731 his situation was so dire that Parliament forced the sale of his Surrey estates.

The Great Park was sold to John Walter, Grafton's former steward, and in 1750 was sold in chancery to William Taylor who established the Malden Powder Mills. The Little Park was sold to Joseph Thompson. On his death in 1743 the estate passed to his nephew, Joseph Whateley on the condition he take holy orders. It was Joseph's brother Thomas who resided at Nonsuch. Thomas was interested in landscape gardening and it is likely that he began to set out the gardens at Nonsuch. When Joseph died in 1797 his will instructed the sale of the site. The estate was finally bought in 1799 by Samuel Farmer.

.

.